Musician Phil Cunningham's BBC programme 'The narrow sea, the farthest shore' (2022) explores the cultural links between the west of Scotland and the north east of Ireland across the Narrow Channel. Islay is mentioned a number of times and in particular the skipper of a boat who regularly travels this journey today tells him about a turbulent stretch of water by Rathlin Island, near Ballycastle in County Antrim:

'This particular place is just known as MacDonnells Race* because when you get a fast flow of water it is known as a race. A family of four brothers went over to Islay to celebrate and get all the goods they needed and on the way back they hit a very bad piece of very fast water and the boat sunk on them and the four brothers were drowned so they christened if after them'

Of course that got me searching for details of this tragic event. Another version of the tale is given by Anne Winter in her account of sailing between Islay and Rathlin Island in 2019: 'We could see rough water to the north east of the headland: the MacDonnell race, named after the MacDonnell brothers, who were drowned returning to Rathlin when they were caught in a vicious tide race. Their father watching from land raised his arm as if to move the boat’s tiller to steer them out of harm’s way. Legend has it that his arm stayed in the same position for the rest of his life'. Winter mentions visting the Rathlin Island Boathouse museum so assume she picked up this story there.

The name goes back to at least the mid-19th century. The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle published an article in February 1856 on 'Rathlin Sound and General Directions for the North Channel, Ireland' by R. Hoskyn, Admirality Surveyor for the NE Coast of Ireland. Hoskyn writes that 'Off Altacarry Head a rocky bank extends two thirds of a mile to the northward; where from thirty fathoms it deepens to ninety in a distance of two cables further. The tide, in its passage across it forms a race known as McDonald Race'. 'Sailing Directions for Ireland' published by the United States. Hydrographic Office (1934) likewise warn of 'overfall extending 1350 yards from the shore, called Macdonald Race'

I haven't found any specific historical report of the four drowned brothers, perhaps it is a local legend based on an actual happening more than 170 years ago, though there are other strong historical connections between Rathlin and the MacDonald name. Rathlin Castle was the base for the MacDonnells (sometimes spelt MacDonalds) in their bid for control of parts of Antrim, ended by an infamous massacre in 1575 when English forces led by John Sorreys and Francis Drake stormed the island. The MacDonnells had branched off from the Islay based MacDonalds of Dunyvaig. That's another story but it shows how the history of Islay is bound up with happenings in Ireland just as much as in Scotland.

In any event, newspaper reports do list plenty of maritime tragedies with Rathlin and Islay connections.

For instance, in 1856 a Mr Mann of Portrush was on his was way by sea to Islay when he found an upturned boat. There was no sign of the crew, believed drowned after capsizing on their way from Ballycastle to Rathlin (Belfast Morning News, 10/6/ 1858). In 1917 a Rathlin Island fireman, M'Guilkin was one of three seamen who drowned when the Clyde Shipping Company's tug Flying Falcon was caught in a storm off Islay (Londonderry Sentinel, 11/10/1917).

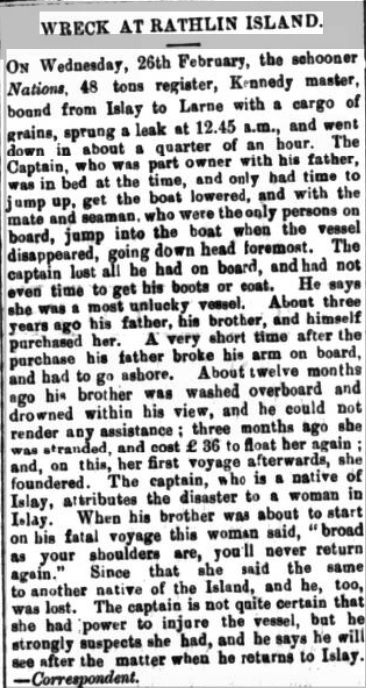

The wreck of the schooner Nations at Rathlin Island was reported in the Ballymoney Free Press (11/3/1880), with the boat going down on its way from Islay to Larne with a cargo of grain. The crew survived, though the Captain's brother had been drowned a year earlier after being washed overboard from the same boat. The captain pronounced the boat to be 'an unlucky vessel' and intriguingly seems to blame the prophesy of an Islay woman: 'The captain, who is a native, attributes the disaster to a woman in Islay. When his brother was about to start on his fatal voyage this woman said "broad as your shoulders are, you'll never return again". Since that she said the same to another native of the Island and he too was lost. The captain is not quite certain that she had the power to injure the vessel, but he strongly suspects she had'. That raises the whole folklore of 'the sight' in Islay, in particular the ability to predict somebody's death, another interesting topic in its own right.

* The spelling is variously given in different places as MacDonnell, McDonnell, McDonald, MacDonald or any of the above with an s a the end.

Update - On twitter (30/1/22) Douglas Cecil, a Rathlin Islander and ferry skipper, tells me that 'there is a small stone cairn built on the cliffs of the North Side of Rathlin which looks directly across to McDonnells Race where the father was said to have been keeping a lookout from'